|

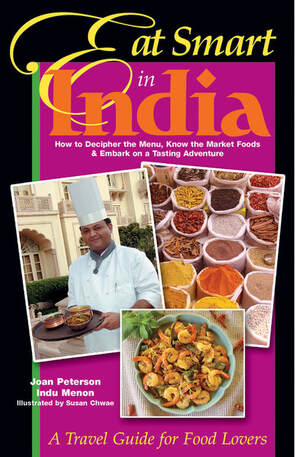

by Joan Peterson, publisher and co-author of Eat Smart in India: How to Decipher the Menu, Know the Market Foods, & Embark on a Tasting Adventure  Spices and herbs are the cornerstone of Indian cookery. Traditionally they are freshly ground twice a day in a shallow stone mortar or on a flat basalt stone using a basalt rolling pin. Chefs and home cooks alike are well versed in the individual characteristics of each seasoning. They know which spices enhance the flavors of particular foods, how much of each spice should be added to a dish, and in what order spices should be added in the cooking process so that no spice predominates or tastes “raw.” Artful blending of different seasonings has created the subtle nuances in the characteristic tastes of Indian cuisine. In general, spice mixtures (masalas) are either wet or dry. Wet mixtures are moistened with water, oil, vinegar or coconut milk to make a paste or more liquid mixture, and they cannot be stored. Dry mixtures mainly are powdered. In Indian cooking there is no all-purpose curry powder. This is a commercial mixture created during colonial times by the British, who still use it rather indiscriminately to make “Indian” dishes. To an Indian, a curry (kari) is a sauce, or a dish with sauce. Wet mixtures of fresh spices predominate in southern Indian cooking. Here the main staple is rice, and although it typically is boiled and eaten plain, several flavored sauces accompany the rice to moisten it. In northern Indian cooking, many dishes tend to be cooked without much liquid, and as such are easier to scoop up with pieces of bread as a utensil. Without sauce to cook in, spices are tempered in a small amount of clarified butter or oil to release their aromas before the main ingredients are added to the pan. In some recipes, tempered spices are added at the end of the cooking process.

Indians favor the visual appeal of certain spices. Turmeric gives a bright yellow color to rice and potatoes. The very expensive saffron lends an orange-yellow color besides its incomparable, heady flavor. Mild red chile peppers grown in Kashmir are prized for the rich red color they impart. Another red colorant, an edible extract called mowal, is made by boiling cockscomb flowers. Dried rind of the red mango (kokum) turns food somewhat pinkish-purple. We especially like the refreshing, slightly tart drink (kokum kadi) of fresh coconut milk flavored with this rind.  Fresh sprig of fragrant curry leaves. Sizzling the leaves in a little oil accentuates their aroma and slightly bitter taste. This spice provides a signature flavor to southern Indian dishes. Fresh sprig of fragrant curry leaves. Sizzling the leaves in a little oil accentuates their aroma and slightly bitter taste. This spice provides a signature flavor to southern Indian dishes. Among the unusual spices to experience is asafoetida (hing), a strong, sulfur-smelling, milky gum resin. A pinch of powdered resin cooked in hot oil or clarified butter and added to certain dishes enhances the flavor. A trace of the odor component of the resin lasts for a short while in the food. Curry leaves (kari patta) are small, dark-green leaves with a distinct aroma and slightly bitter taste. They are sizzled in a little clarified butter or oil to accentuate their flavor. Fenugreek leaves (kasoori methi) have a unique, slightly bitter flavor. It is an acquired taste, which can be sampled in aloo methi, diced potatoes fried with fresh fenugreek leaves. Bits of dried fenugreek leaves occasionally are added to flatbread dough. Kewra essence is extracted from the flowers of the screwpine and is used in rice- or corn-flour noodles called falooda. These flavored noodles are an ingredient in a drink, which is also called falooda, and they accompany Indian ice cream made with reduced milk. Certain lichens are used as herbs. Kalpasi is a lichen that grows on cinnamon trees and on trees near the seashore during the monsoon.  Several kinds of salt are used in Indian dishes. Some are flavored salts mined as crystals from underground dry sea beds. Each imparts a characteristic flavor based on its chemical composition. For example, black mineral salt (kala namak) adds zest to snacks (chaat), fruit salads and vegetables. Its grayish-pink crystals become grayish-brown when ground. Countless outdoor markets exist in India. There will be many opportunities to see all the amazing spices that are used in Indian cookery.  photo: cookingandme.com photo: cookingandme.com Enai Katrikey Aromatic sautéed eggplant. Serves 4. 4 T. vegetable oil 1 1/2 lbs. baby eggplants, each cut into 4 pieces 1 small onion, chopped 1 clove garlic, sliced 1 T. grated fresh ginger 1/2 t. cumin seeds 1 t. black mustard seeds 1/2 t. black peppercorns 1-inch piece cinnamon stick 1/2 c. grated fresh coconut 4 dried, hot red chile peppers 1 T. coriander seeds 1 t. fennel seeds 1 t. star anise 4 whole cashew nuts 1 T. coconut oil 10 curry leaves 1/4 t. turmeric powder 1/2 t. salt 3/4 c. water Heat oil in a frying pan and sauté eggplant until soft. Remove from the pan and set aside. Fry onion, garlic and ginger for 1–2 minutes over high heat, and set aside. In the same pan, dry roast cumin, 1⁄2 teaspoon mustard seeds, peppercorns, cinnamon, coconut, two red chile peppers, coriander, fennel, star anise and cashew nuts until dark brown. Let cool. Grind dry-roasted spices with fried onion, garlic, ginger, and 1⁄4 cup water into a fine paste and set aside. Heat coconut oil in a frying pan over high heat until shimmering. Add 1⁄2 teaspoon mustard seeds, two red chile peppers and curry leaves. Cover the pan and let seeds sputter. When sputtering slows down, remove spices from the pan and set aside. Return partly cooked eggplant to the pan. Add turmeric, salt, spice paste and 1⁄2 cup water. Mix well and cook for 5 minutes over medium heat or until the eggplant is completely cooked. Garnish with fried mustard seeds, red chile peppers and curry leaves.

7 Comments

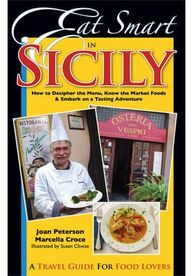

The following is an excerpt from Eat Smart in Sicily, by Joan Peterson and Marcella Croce, published by Ginkgo Press, Inc. To purchase Eat Smart in Sicily, click here.  Photo credit: Wikipedia Photo credit: Wikipedia Sicily passed into the hands of Arab Muslims in 902 after a long, determined campaign. Arab raids on Byzantine Sicily began as early as the 7th century. The island of Pantelleria fell in 700. An invasion in 827 near Mazara del Vallo on the southwestern coast of Sicily was successful, and more cities were taken. But several subsequent sieges were necessary before they obtained complete control of the island in 902. Sicily became an emirate, with Palermo its capital, from which the Arabs ruled until 1091. Palermo became adorned with mosques and minarets alongside cathedrals. Under the Arabs’ watch, Sicily became one of the wealthiest and most progressive cultures of medieval Europe. The followers of Islam, also known as Saracens, began their assault on Sicily from modern-day Tunisia in North Africa. The group was comprised of Arabs originally from the Arabian peninsula, Spanish Muslims and the indigenous Berbers of North Africa, converts to the Muslim faith. They were destined to have a profound influence on Sicily and her cuisine. The Arabs introduced advanced irrigation technology and revolutionized existing agricultural practices. They constructed canals to bring water from springs and rivers to agricultural areas and cities. In the cities, a network of underground tunnels (kanat) was dug, with the tunnels sloped downward for gravity-based water flow. This water system also fed city gardens and fountains. Remnants of these ancient tunnels still exist in some of the old parts of Palermo. Arabs added a wide variety of new crops and were able to cultivate them on a large scale because of the improvements they had made in water availability. They broke up many of the vast feudal estates, the latifundia, into smaller farms and gardens, freeing the farmers who worked the plots from indentured servitude. Orchards of lemons, oranges, almonds, pistachios and mulberries were established. Sugar cane was grown in the flat coastal areas. Date palms and carob trees were planted. Rice was introduced and was grown in paddies in the eastern part of the island near Lentini. Other new vegetables, fruits and spices brought by the Arabs included eggplant, artichoke, melon, apricot, banana, buckwheat, cumin, tarragon, jasmine and a white grape variety called zibibbo, which later would be used to make sweet wines. Some scholars theorize that Arabs also introduced to Sicily the “naked” wheat variety known as durum wheat, asserting that it had not been grown, at least to any great extent, during Greek and Roman times when Sicily’s extensive output of wheat was of a different “naked” variety known as soft bread wheat. We can leave this matter of debate to molecular archaeologists, because the salient point is that the Arabs introduced some foods of great significance that were made from the hard-grained durum wheat. The most far-reaching of them was dried pasta (pasta secca). Due to its high gluten content, dough made from durum wheat is strong. It can be rolled and cut into many forms that maintain their shapes and patterns, and lasting ridges can be impressed on the surface. When dried, the pasta does not spoil, thus making it suitable for long-term storage and transport. It had been known to the Arabs since about the 8th century. The Arabic word itriyya referred to long, thin strings of dough that were dried before boiling. Itriyya had a tremendous influence on the island’s foodways and far beyond. We know that by the 12th century dried pasta products were manufactured in Sicily for export. Al-Sharif al-Idrisi, an esteemed cartographer in the employ of Roger II, King of the Normans—whose father conquered Sicily and ended Arab rule—was commissioned to create an elaborate map of the world as it was then known. It was to be accompanied by a book detailing, among other things, commerce and production in all the locations shown on the map and visited by al-Idrisi in the 15 years he spent on the project. The map and book, interestingly entitled, A Diversion for the Man Longing to Travel to Far-off Places, were completed in 1154. The book records the presence of mills in the town of Trabia on the northern coast, near Palermo, which were making commercial preparations of dried pasta and shipping large quantities of it to the rest of Europe. Arabs brought the art of making couscous, a painstaking process the Sicilians call incocciata, which involves rolling fine grains of durum wheat (semolina) in circles in a flat bowl while moistening it with water to form small, uniform granules. The granules are cooked by steaming over broth. In North Africa, couscous usually is topped with a meat stew. But in Sicily, where fish are bountiful, couscous typically is topped with fish. In western Sicily, where the Arabic influence was particularly strong—especially in the city of Trapani—this dish (cuscus alla Trapanese or cuscus di pesce) continues to be popular. Skewered and stuffed foods were also a part of the Arab legacy. Typical stuffing combinations include dried currants with bread crumbs. The embodiment of this kind of preparation is involtini alla Siciliana, Sicilian skewered meat rolls. Thin slices of veal or beef are rolled around a mixture of toasted bread crumbs, pine nuts, dried currants and cheese. Three or four of these rolls, interspersed with slices of onion and bay leaves, are placed on a skewer and grilled. The Sicilian sweet tooth was diversified by the Arab’s gift of sugar cane. Prior to this time, honey and a syrupy reduction of grape juice (vino cotto) were used as sweeteners. Each has a distinct flavor that tends to dominate in dishes. The use of cane sugar allowed for the creation of sweets with subtler flavors contributed by other ingredients. Cannoli (“pipes”), arguably Sicily’s most famous dessert innovation with Arab roots, are crispy, fried, hollow tubes made of dough flavored with cinnamon. The addition of wine to the dough creates little air pockets that form and break during frying, giving the shells their characteristic pock-marked surface. The tubes are filled with sweetened ricotta cream, and the ends are decorated with some candied fruit. Cassata, the queen of Sicilian cakes, is assembled from layers of sponge cake and sweetened ricotta cheese surrounded by a shell of marzipan tinted pale green. The cake is iced and lavishly decorated with candied fruit and zucchini preserves. Marzipan itself has an Arab heritage and is used in many confections besides cassata. Most notable are the molded, vividly colored marzipan fruits. Sugary frozen fruit treats were another Arab contribution. A sorbetto (from the Arabic sciarbat), or sorbet, is a frozen, water- based dessert, typically made with fruit juice and puréed fruit In early times a sorbetto was concocted from the juice of citrus fruits and snow brought from the slopes of Mt. Etna. A variation is the granita, a refreshing drink of flavored, crushed ice. The Arabs left their imprint on the ritual of bluefin tuna fishing, an important industry in the Mediterranean since prehistory. Ensnaring tuna in some form of complex, giant undersea trap (tonnara) comprised of interconnected chambers made of net may have originated as early as Phoenician times. Arabs contributed some of the terminology of the tonnara as well as the music of the traditional songs and chants the men sang as they worked. Annually, in anticipation of the spawning migrations, the Arabs assembled a seven-chambered trap west of Sicily in the waters off Favignana, the southernmost of the Egadi Islands. The rais (Arabic for “head”) led his crew of fishermen in carrying out the mattanza (Spanish for “killing”). First he determined that the migrating fish were successfully herded through the chambers via inter-chamber gates to the seventh and final chamber, the “Chamber of Death.” This chamber had a net floor, which then was slowly raised, bringing the fish to the surface. Crowded together without possible escape and wildly thrashing, the fish were dispatched with barbed gaffs and hauled away. Today, overfishing has all but ended the capture of bluefin tuna in the Mediterranean. Involtini di Lampuga Stuffed fish (mahi-mahi) rolls. Serves 2. This recipe was provided by Vincenzo Barranco, owner and former chef of the popular Ostaria del Duomo in Cefalù. Mr. Barranco’s sons also work in the restaurant: Davide is the chef and Allesio is the maitre d’hotel. The Ostaria del Duomo specializes in seafood dishes and has an enviable location in front of the Duomo. 3/4-1 pound Mahi-Mahi fillet 6 T. Olive il 3 T. Onion, chopped 1 T. Dried black currants 2 t. Pine nuts 2/3 c. Bread Crumbs Salt to taste Toothpicks to secure fish rolls 1 Clove garlic, coarsely chopped 8-10 Cherry tomatoes, quartered Capers for garnish Chopped parsley for garnish Have your fishmonger cut fish on the diagonal every 3 inches to produce thin slices. Gently pound to flatten so each piece is 3" × 4" and about 1/4" thick. To make stuffing, heat 3 tablespoons of olive oil over medium heat in a small frying pan. Add onion and fry until limp. Add currants and pine nuts and cook for 5 minutes, stirring frequently. Add bread crumbs and salt to taste. Stir well and remove pan from heat. Place about 2 tablespoons of the stuffing in a strip near one of the short edges of each piece of fish. Starting with this end, roll fish around the stuffing and secure each roll with a toothpick. Heat remaining olive oil in a frying pan over medium-high heat. Add garlic and sauté until golden. Add tomatoes. When they soften, mash them gently with a spoon. Add fish rolls and sauté, covered, about 5 minutes or until fish flakes easily, turning rolls occasionally. Remove rolls to a platter and spoon the tomato sauce over the top. Garnish with some capers and parsley. Serve immediately. 2018 Gourmand Cookbook Awards

Best Culinary Travel Guidebook Series in the World 2008 National Best Books Awards Winner- Travel Guides - USABookNews.com 2009 Next Generation Indie Book Award Finalist - Travel/Travel Guides Eric Hoffer Book Award First Runner Up - Reference/Travel 2008 from Planeta.com Winner - Best Food Guidebook of the Year |

AuthorWe write about food and travel. CategoriesArchives

October 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed